Sigiriya Rock can be explored in two to three hours; early morning or late afternoon are the best times to go because it’s cooler outside and there are fewer visitors. The dramatic orange hue of the rock, evocative of Asia’s Ayers Rock, is further emphasised by the late afternoon light.

Table of Contents

- Where is Sigiriya?

- Visiting Sigiriya rock fortress

- What are the popular tour packages to visit Sigiriya?

- A brief history of Sigiriya

- Sigiriya rock fortress

- The Water Gardens

- The Boulder Gardens

- Terrace Gardens

- The Sigiriya Frescoes

- “The Mirror Wall”

- The Lion Background

- The summits

- Pidurangala’s Royal Cave Temple

Where is Sigiriya?

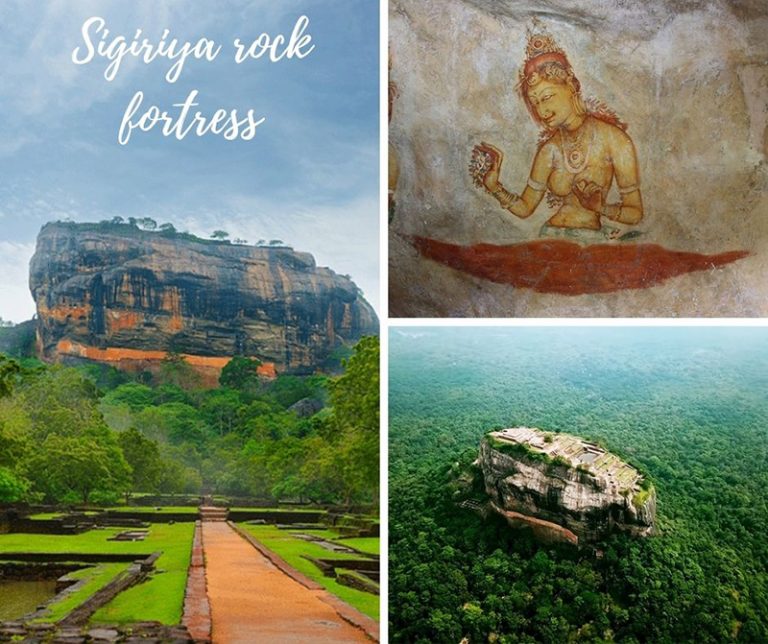

Situated around 15 km northeast of Dambulla, the majestic citadel of SIGIRIYA is positioned atop a large outcrop of gneiss granite that rises 200 metres above the surrounding terrain, rising high and impenetrable out of the arid plains of the dry zone. Sigiriya, often called “Lion Rock,” is the most remarkable and fleeting of all Sri Lanka’s mediaeval capitals. It was named a World Heritage Site in 1982 and is the most unforgettable sight in the country. The striking surroundings of this incredible archaeological site add to its memorability.

Visiting Sigiriya rock fortress

Venturing on a Sigiriya tour is the best way to explore this fascinating historical site in Sri Lanka. Sigiriya can be explored on a standalone trip, such as a Sigiriya one-day tour from Colombo. The Sigiriya tour can also be combined with many other itineraries, such as the Sri Lanka 10-day tour, the Sri Lanka 7-day tour, or the Sri Lanka 5-day tour. Most tour itineraries include Sigiriya, and a tour itinerary of Sri Lanka without Sigiriya is largely incomplete because it is a must-visit historical site in Sri Lanka.

What are the popular tour packages to visit Sigiriya?

Every cultural triangle tour includes Sigiriya Rock Fort along with many other historical and cultural tourist attractions in the cultural triangle. Here are 5 popular activities offered by the Seerendipity tour.

- Sigiriya Dambulla one day tour with Minneriya national park

- Glimpse of Sri Lankan culture

- Sri Lanka history and culture tour

- Splendid Sri Lanka 5-day tour

- Beaten path Sri Lanka 7-day tour

A brief history of Sigiriya

Inscriptions found in the tunnels that entwine with the base of the rock indicate that Sigiriya served as a place of religious seclusion as early as the third century BC, when Buddhist monks established refuges here. But it wasn’t until the 5th century AD—during the power struggle that terminated Dhatusena’s (455–473) hegemony over Anuradhapura—that Sigiriya briefly rose to prominence in Sri Lankan history. Dhatusena had two sons: Mogallana, by the most illustrious of his various queens, and Kassapa, by a lesser consort. Upon discovering that Mogallana had been declared the heir apparent, Kassapa rebelled, imprisoning his father and sending Mogallana into exile in India. Dhatusena agreed to give his son the location of the wealth in exchange for letting him have a final swim in the majestic Kalawewa Tank, which he had overseen, out of fear for his life if he did not reveal the location of the state treasure. Standing in the tank, Dhatusena poured the water through his hands before telling Kassapa that the water constituted all of his treasure. Kassapa, unimpressed, locked his father in a room and left him to die.

Mogallana pledged to return from India and get his riches in the interim. Around the base of the 200-meter-tall Sigiriya Rock, which Kassapa had erected as a temporary capital and fortress in anticipation of the approaching invasion, a new city was constructed. The house was meant to seem like the mythological Kubera, the god of prosperity. According to tradition, the amazing edifice was completed in just seven years, between 477 and 485.

The long-awaited invasion finally happened in 491 because Mogallana gathered an army of Tamil mercenaries to fight on his behalf. Though Kassapa’s walled citadel gave numerous advantages, in a fatalistic display of valour, he bravely rode out with his warriors on an elephant and bravely descended from his rocky elevation to confront the assault on the plains below. Unfortunately, in the heat of battle, Kassapa’s elephant panicked and fled. He was severed as his soldiers turned around, thinking he was going to withdraw. Just before he was going to be apprehended and vanquished, Kassapa committed suicide.

Following the recapture of Mogallana, Buddhist monks took control of Sigiriya, and pious ascetics seeking seclusion once more crowded the caves there. The place was mostly forgotten until the modern age, when it was finally abandoned in 1155.

Sigiriya rock fortress

Sigiriya Rock can be explored in two to three hours; early morning or late afternoon are the best times to go because it’s cooler outside and there are fewer visitors. The dramatic orange hue of the rock, evocative of Asia’s Ayers Rock, is further emphasised by the late afternoon light. Due to the volume of people on the narrow walkways and staircases, it is advised to avoid the site on weekends, especially on Sundays. Though the high ascent may be uncomfortable for those who suffer from vertigo, the walk is not as difficult as it appears from the base of the vertical rock face. Generally, you may hire guides at the entrance. However, it’s a good idea to assess a person’s knowledge and English skills with a few questions before employing them.

The location is split into two sections: the rock where Kassapa constructed his main palace, and the surrounding area with its magnificent royal pleasure gardens and other pre-Kassapa monastery remnants. The intricate paintings of the Sigiriya damsels, which cling to the site’s rocky flanks, are an example of the intriguing fusion of wild nature and lofty artifice. Surprisingly, Kassapa’s Sigiriya doesn’t appear to have had any notable monasteries or other religious buildings, unlike Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa. This might be an indication of its pagan origins.

The Water Gardens

A wide, straight path that runs from the entrance to the rock follows an imagined east-west axis that serves as the layout for the entire site. There are two sizable moats surrounding this side of the rock, but the outer moat is currently largely dry. There are two stories of walls surrounding you as you pass the Inner Moat to enter the Water Gardens. The first section has four square-shaped ponds that fill up to create a little island in the centre. There are pathways connecting the pools and the surrounding gardens. The remains of pavilions are located in the rectangular areas to the north and south of the pools.

Past this section is the small yet well-designed Fountain Garden. Among the characteristics is a little “river” shaped like a serpent. The original sprinkler systems for two ponds and channels with limestone bottoms are still in place. A simple idea based on pressure and gravity allows the small water plumes of the fountains to be seen after heavy rains, even after over 1500 years of dormancy. Restoring the fountains to working order was all that was needed to clear the water pipes that supply them.

The Boulder Gardens

After leaving the Water Gardens, the main road begins its ascent past the Boulder Gardens, which are composed of enormous boulders that have fallen along the base of the cliff. There are lines of holes etched into several of the boulders, creating the illusion that the rock steps are there. On top of or against the boulders, however, these footings provided support for the numerous buildings that were built, whether they were timber frames or brick walls.

Before and after Kassapa, the gardens functioned as the focus of Sigiriya’s monastic existence. The monks used about twenty rock shelters, some of which had inscriptions dating back to the first or third century AD. As you enter each cave, you’ll discover that dripstone ledges surround the openings to prevent water from entering. In certain places, traces of the original painting and plastering that adorned the caverns can still be seen. The Deraniyagala Cave lies to the left (no sign) just after the trail begins to rise up through the gardens. Here are traces of old murals, including faded pictures of various apsara figures (celestial nymphs) that resemble the famous Sigiriya Damsels further up the rock, as well as a well-preserved dripstone ledge. A minor track that splits off from the main route up the cliff leads to the Cobra Hood Cave, so named because of its remarkable likeness to the head of that snake. The cave contains fragments of lime plaster, floral designs, and a very weak inscription in Brahmi script from the second century BC on a ledge.

After continuing the trail that climbs the slope below the Cobra Hood Cave and goes through “Boulder Arch No. 2” (as indicated by signage), turn left to reach the so-called Audience Hall. The walls and roof of the wooden house have long since disappeared, leaving only the floor, which was remarkably smoothed by chipping the top of a single, gigantic boulder, and a 5-meter-wide “throne” fashioned in a similar manner out of solid rock. The hall is called Kassapa’s audience hall; however, it is more likely to have served a strictly religious role (the vacant throne symbolises the Buddha). A few other thrones are carved into nearby rocks, and the little Asana Cave, which is accessible via the route that leads to the Audience Hall, still has some colourful splashes of various paintings on its top, despite the fact that current graffiti has almost entirely covered them.

Terrace Gardens

After leaving the Asana Cave, you can go back to the main road and proceed uphill by “Boulder Arch No. 1”. The Terrace Gardens, a series of brick and limestone terraces that stretch to the base of the cliff and offer the first of many stunning views of the panorama below, are where the walkway—now a set of walled-in steps—begins its steep ascent.

The Sigiriya Frescoes

Soon after reaching the base of the cliff, two dissonant nineteenth-century spiral staircases made of metal lead to and from a protected cave in the sheer rock face, which houses the Sigiriya Paintings, the most famous mural series in Sri Lanka (no flash photography). These busty beauties, which date back to the fifth century and are the only non-religious paintings from ancient Sri Lanka that have survived, have become one of the most recognisable and often imitated images on the island. The original approximately 500 paintings of these frescoes are thought to have covered an area of around 140 metres by 40 metres in height; however, only 21 paintings are thought to remain (many were damaged by a vandal in 1967, and some of the remaining paintings are hidden behind ropes). The precise meaning of the paintings is unclear, although it was once thought they depicted Kassapa’s consorts. The most plausible theory, according to modern art historians, is that the paintings are portraits of apsaras, or celestial nymphs; this would explain why they are only seen rising from a cloud cocoon from the waist up. Unlike the much later and more stylized murals at neighbouring Dambulla, the representation of the damsels is astonishingly lifelike, with them spreading petals and giving trays of fruit and flowers. The design is similar to the famous murals seen in India’s Ajanta Caves. The occasional brush slip reveals that one damsel has three hands and another has an extra nipple, which adds a beautifully human touch.

“The Mirror Wall”

The Mirror Wall encloses one side of the walkway, which follows the rock face just past the damsels. A portion of the original plaster has remained and maintains an incredible glossy sheen. The original plaster was covered in a highly polished plaster made of egg white, beeswax, lime, and wild honey. Graffiti abounds on the wall, with the oldest pieces dating back to the seventh century. The first visitors used these to write down their opinions of Sigiriya, particularly regarding the local damsels. Those who were interested in witnessing the ruins of the old city continued to go to Sigiriya, even after Kassapa’s splendid pleasure dome was abandoned. When put together, the graffiti resembles a visitors’ book from the early Middle Ages, and the about 1500 understandable comments offer important new insights into the development of the Sinhala language and script.

The path continues past the Mirror Wall onto an iron footbridge that seems menacing because it is fixed onto the sheer rock face. This vantage point shows a large rock resting on slabs of stone below. The traditional notion is that in the event of an attack, the slabs would have been knocked away, forcing the boulder to fall upon the assailants below, though it’s more likely that the slabs were intended to prevent the rock from inadvertently toppling over the cliff.

The Lion Background

A steep flight of limestone steps further up the rock leads to the Lion Platform, a sizable spur that rises from the north side of the rock just below the top. A last staircase leads up past the remnants of a huge statue of a lion with two enormous paws carved out of the rock at its feet. The route to the summit seems to have gone directly into the statue’s mouth. One imagines that the beast’s massive conceit and rich symbolism sufficiently astonished Kassapa’s visitors. The most important symbol of Sinhalese royalty was a lion, and Kassapa’s size was probably used to symbolise his rank and legitimise his illusory claim to the throne.

Ironically, it seems that Kassapa had a fear of heights, and it is believed that a tall wall would have surrounded these steps in the beginning. Nevertheless, this brings little comfort to contemporary vertigo patients, as they have to ascend a slender iron ladder affixed to the exposed rock face in order to reach the peak. Numerous striations and grooves adorn the entire length of rockface above, which formerly held steps leading to the summit.

The summits

At the top of the steep climb, it looks gigantic. This was Kassapa’s palace, and at one point, buildings practically filled the entire area. Now all that’s left are the foundations, and it’s difficult to make sense of it all; the main attraction is the breathtaking view down to the Water Gardens and across the surrounding countryside. Today, the Royal Palace is only a plain, square brick platform perched at the very top of the cliff. The highest portion is surrounded by sloping terraced walls, under which is a large rock-hewn tank; water was supposedly diverted to the summit by a sophisticated hydraulic system powered by windmills. Four further terraces, which were presumably formerly gardens, slope to the foot of the mountain above Sigiriya Wewa below this point.

After leaving the site to the south, you should ultimately pass the Cobra Hood Cave on your right if you missed it earlier. The descent takes a somewhat different route.

Top-bee conduct

The little cages made of wire mesh that you see on Sigiriya’s Lion Platform were built as a protective structure in case of bee attacks, which have occurred recently despite efforts (using a mix of chemical and ceremonial exorcism) to drive the offending insects from their nests, which are visible clinging to the underside of the rock overhang above, to the left of the stairs. Local Buddhist monks claim that these attacks are divine retaliation for tourists’ impious behaviour.

Pidurangala’s Royal Cave Temple

Situated a few kilometres north of Sigiriya, on yet another enormous rock outcrop, is the Pidurangala Royal Cave Temple. It is stated that Kassapa founded the monastery here by erecting new residences and a temple in order to make up for the monks who were forced to relocate from Sigiriya to make room for the king’s palace. Continue north of Sigiriya for about 750 metres to the Pidurangala Sigiri Rajamaha Viharaya, a white, contemporary temple. The short bike or tuktuk journey to the foot of Pidurangala Rock is enjoyable. There are also some intriguing remnants of some old monastic buildings, including the ruins of a sizable brick dagoba, some 100 metres further up this path on the left. The Royal Cave Temple is located on a platform just below the peak of the rock, accessible via steep stairs that ascend the slope behind the Pidurangala Viharaya. A long, reclining Buddha statue with part of its upper half reconstructed in brick is the only sight in the imposingly named temple. It takes roughly fifteen minutes to climb steeply. Fading murals with depictions of Vishnu and Saman accent the statue’s exterior.

It’s simply a 5-minute scramble to the summit of the rock if you can find the rocky track that leads there. You’ll need to be physically fit and agile to make sure you don’t get lost on the surprisingly easy return. The best view of Sigiriya you’ll find short of renting a balloon awaits your efforts. It will reveal the northern face of the rock, which is obscured from view throughout the ascent but has a significantly more fascinating shape and irregularity. Nearly level with you, the ant-like figures of individuals making the final trek to the summit are scarcely discernible against the enormous slab of red rock.